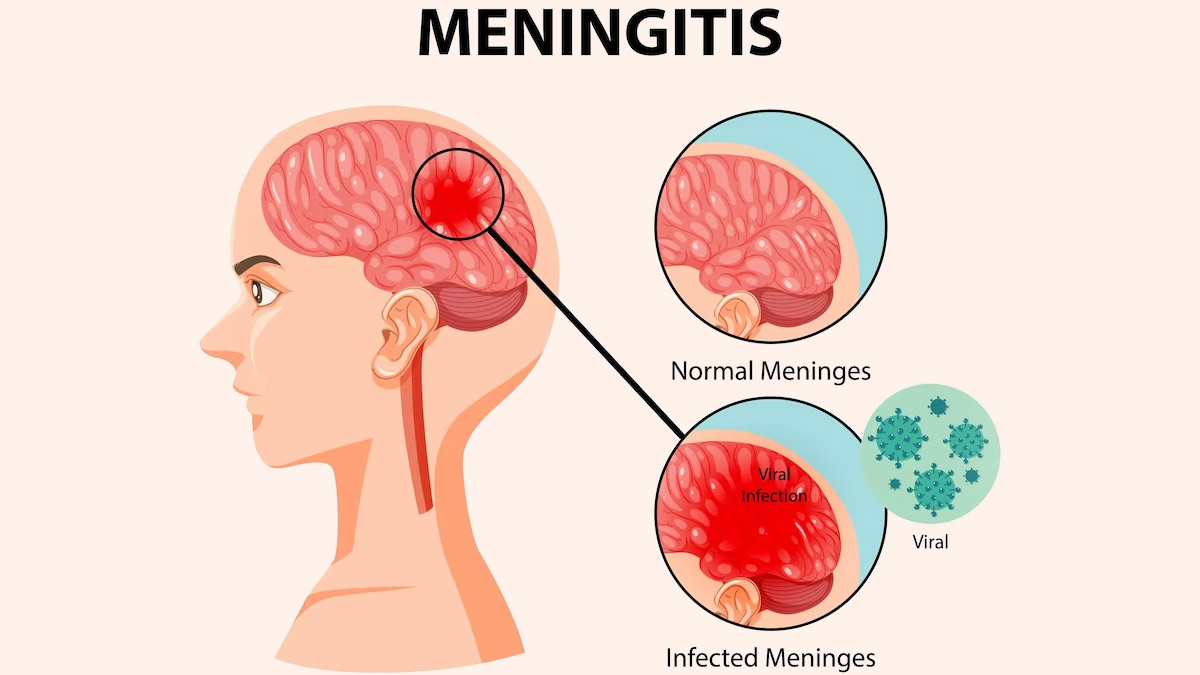

Meningitis

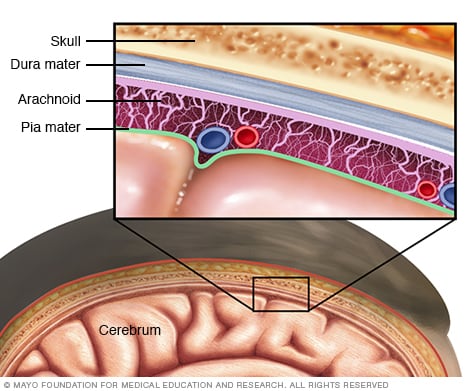

Meningitis is an inflammation of the membranes (meninges) surrounding your brain and spinal cord. The swelling typically triggers symptoms such as a headache, fever and a stiff neck. Most cases of meningitis are a viral infection, but bacterial and fungal infections are other causes. Some cases improve without treatment in a few weeks. Others can be life-threatening and require emergent antibiotic treatment.

Possible signs and symptoms in anyone older than the age of 2 includes:

- Sudden high fever

- Stiff neck

- A severe headache that seems different than normal

- A headache with nausea or vomiting

- Confusion or difficulty concentrating

- Seizures

- Sleepiness or difficulty waking

- Sensitivity to light

- No appetite or thirst

- Skin rash (sometimes, such as in meningococcal meningitis)

Signs in newborns

Newborns and infants may show these signs:

- High fever

- Constant crying

- Excessive sleepiness or irritability

- Inactivity or sluggishness

- Poor feeding

- A bulge in the soft spot on top of a baby’s head (fontanel)

- Stiffness in a baby’s body and neck

Infants with meningitis may be difficult to comfort, and may even cry harder when held.

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical care if you or someone in your family has symptoms, such as:

- Fever

- Severe, unrelenting headache

- Confusion

- Vomiting

- Stiff neck

Bacterial meningitis is serious and can be fatal within days without prompt antibiotic treatment. Delayed treatment increases the risk of permanent brain damage or death.

It’s also important to talk to your doctor if a family member or someone you work with has meningitis. You may need to take medications to prevent getting the infection.

Causes of Meningitis

Viral infections are the most common cause of meningitis, followed by bacterial infections and, rarely, fungal infections. Because bacterial infections can be life-threatening, identifying the cause is essential.

- Bacterial

- Bacteria that enter the bloodstream and travel to the brain and spinal cord cause acute bacterial meningitis. But it can also occur when bacteria directly invade the meninges. This may be caused by an ear or sinus infection, a skull fracture, or, rarely, after some surgeries. Several strains of bacteria can cause acute bacterial meningitis, most commonly:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus). This bacterium is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in infants, young children and adults. It more commonly causes pneumonia or ear or sinus infections. A vaccine can help prevent this infection.

- Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus). This bacterium is another leading cause of bacterial meningitis. These bacteria commonly cause an upper respiratory infection but can cause meningococcal meningitis when they enter the bloodstream. This is a highly contagious infection that affects mainly teenagers and young adults. It may cause local epidemics in college dormitories, boarding schools and military bases. A vaccine can help prevent infection.

- Haemophilus influenzae (Haemophilus). Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) bacterium was once the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in children. But new Hib vaccines have greatly reduced the number of cases of this type of meningitis.

- Listeria monocytogenes (listeria). These bacteria can be found in unpasteurized cheeses, hot dogs and luncheon meats. Pregnant women, newborns, older adults and people with weakened immune systems are most susceptible. Listeria can cross the placental barrier, and infections in late pregnancy may be fatal to the baby.

Viral

Viral meningitis is usually mild and often clears on its own. Most cases are caused by a group of viruses known as enteroviruses, which are most common in late summer and early fall. Viruses such as herpes simplex virus, HIV, mumps, West Nile virus and others also can cause viral meningitis.

Chronic

Slow-growing organisms (such as fungi and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) that invade the membranes and fluid surrounding your brain cause chronic meningitis. Chronic meningitis develops over two weeks or more. The symptoms of chronic meningitis — headaches, fever, vomiting and mental cloudiness — are similar to those of acute meningitis.

Fungal

Fungal meningitis is relatively uncommon and causes chronic meningitis. It may mimic acute bacterial meningitis. Fungal meningitis isn’t contagious from person to person. Cryptococcal meningitis is a common fungal form of the disease that affects people with immune deficiencies, such as AIDS. It’s life-threatening if not treated with an antifungal medication.

Other causes

It can also result from noninfectious causes, such as chemical reactions, drug allergies, some types of cancer and inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis.

Risk factors

Risk factors include:

- Skipping vaccinations. Risk rises for anyone who hasn’t completed the recommended childhood or adult vaccination schedule.

- Age. Most cases of viral meningitis occur in children younger than age 5. Bacterial meningitis is common in those under age 20.

- Living in a community setting. College students living in dormitories, personnel on military bases, and children in boarding schools and child care facilities are at greater risk of meningococcal meningitis. This is probably because the bacterium is spread by the respiratory route, and spreads quickly through large groups.

- Pregnancy. Pregnancy increases the risk of listeriosis — an infection caused by listeria bacteria, which also may cause meningitis. Listeriosis increases the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery.

- Compromised immune system. AIDS, alcoholism, diabetes, use of immunosuppressant drugs and other factors that affect your immune system also make you more susceptible to meningitis. Having your spleen removed also increases your risk, and patients without a spleen should get vaccinated to minimize that risk.

Complications

Meningitis complications can be severe. The longer you or your child has the disease without treatment, the greater the risk of seizures and permanent neurological damage, including:

- Hearing loss

- Memory difficulty

- Learning disabilities

- Brain damage

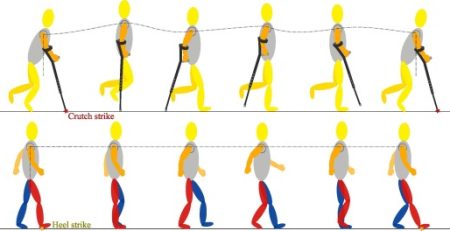

- Gait problems

- Seizures

- Kidney failure

- Shock

- Death

With prompt treatment, even patients with severe meningitis can have a good recovery.

Prevention

Common bacteria or viruses that can cause meningitis can spread through coughing, sneezing, kissing, or sharing eating utensils, a toothbrush or a cigarette.

These steps can help prevent meningitis:

- Wash your hands. Careful hand-washing helps prevent germs. Teach children to wash their hands often, especially before eating and after using the toilet, spending time in a crowded public place or petting animals. Show them how to vigorously and thoroughly wash and rinse their hands.

- Practice good hygiene. Don’t share drinks, foods, straws, eating utensils, lip balms or toothbrushes with anyone else. Teach children and teens to avoid sharing these items too.

- Stay healthy. Maintain your immune system by getting enough rest, exercising regularly, and eating a healthy diet with plenty of fresh fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

- Cover your mouth. When you need to cough or sneeze, be sure to cover your mouth and nose.

- If you’re pregnant, take care with food. Reduce your risk of listeriosis by cooking meat, including hot dogs and deli meat, to 165 F (74 C). Avoid cheeses made from unpasteurized milk. Choose cheeses that are clearly labelled as being made with pasteurized milk.

Immunizations

Some forms of bacterial meningitis are preventable with the following vaccinations:

- Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) vaccine. Children should receive this vaccine as part of the recommended schedule of vaccines, starting at about 2 months of age. The vaccine is also recommended for some adults, including those who have sickle cell disease or AIDS and those who don’t have a spleen.

- Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). This vaccine also is part of the regular immunization schedule for children younger than 2 years. Additional doses are recommended for children between the ages of 2 and 5 who are at high risk of pneumococcal disease, including children who have chronic heart or lung disease or cancer.

- Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). Older children and adults who need protection from pneumococcal bacteria may receive this vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the PPSV vaccine for all adults older than 65, for younger adults and children age 2 and up who have weak immune systems or chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes or sickle cell anaemia, and for those who don’t have a spleen.

- Meningococcal conjugate vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that a single dose is given to children ages 11 to 12, with a booster shot given at age 16. If the vaccine is first given between ages 13 and 15, the booster shot is recommended between ages 16 and 18. If the first shot is given at age 16 or older, no booster is necessary. This vaccine can also be given to younger children who are at high risk of bacterial meningitis or who have been exposed to someone with the disease. It’s approved for use in children as young as 9 months old. It’s also used to vaccinate healthy but previously unvaccinated people who have been exposed to outbreaks.

Diagnosis

Your family doctor or paediatrician can diagnose based on a medical history, a physical exam and certain diagnostic tests. During the exam, your doctor may check for signs of infection around the head, ears, throat and the skin along the spine.

You or your child may undergo the following diagnostic tests:

- Blood cultures. Blood samples are placed in a special dish to see if it grows microorganisms, particularly bacteria. A sample may also be placed on a slide and stained (Gram’s stain), then studied under a microscope for bacteria.

- Imaging. Computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) scans of the head may show swelling or inflammation. X-rays or CT scans of the chest or sinuses may also show infection in other areas that may be associated with meningitis.

- Spinal tap (lumbar puncture). For a definitive diagnosis of meningitis, you’ll need a spinal tap to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In people with meningitis, the CSF often shows a low sugar (glucose) level along with an increased white blood cell count and increased protein.CSF analysis may also help your doctor identify which bacterium caused meningitis. If your doctor suspects viral meningitis, he or she may order a DNA-based test known as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification or a test to check for antibodies against certain viruses to determine the specific cause and determine proper treatment.

Treatment

The treatment depends on the type you or your child has.

Bacterial

Acute bacterial meningitis must be treated immediately with intravenous antibiotics and, more recently, corticosteroids. This helps to ensure recovery and reduce the risk of complications, such as brain swelling and seizures.

The antibiotic or combination of antibiotics depends on the type of bacteria causing the infection. Your doctor may recommend a broad-spectrum antibiotic until he or she can determine the exact cause of meningitis.

Your doctor may drain any infected sinuses or mastoids — the bones behind the outer ear that connect to the middle ear.

Viral

Antibiotics can’t cure viral meningitis, and most cases improve on their own in several weeks. Treatment of mild cases of viral meningitis usually includes:

- Bed rest

- Plenty of fluids

- Over-the-counter pain medications to help reduce fever and relieve body aches

Your doctor may prescribe corticosteroids to reduce swelling in the brain, and an anticonvulsant medication to control seizures. If a herpes virus caused your meningitis, an antiviral medication is available.

Other types of meningitis

If the cause of your meningitis is unclear, your doctor may start antiviral and antibiotic treatment while the cause is determined.

Chronic meningitis is treated based on the underlying cause. Antifungal medications treat fungal meningitis and a combination of specific antibiotics can treat tuberculous meningitis. However, these medications can have serious side effects, so treatment may be deferred until a laboratory can confirm that the cause is fungal. Chronic meningitis is treated based on the underlying cause.

Noninfectious meningitis due to an allergic reaction or autoimmune disease may be treated with corticosteroids. In some cases, no treatment may be required, because the condition can resolve on its own. Cancer-related meningitis requires therapy for individual cancer.

Preparing for your appointment

Meningitis can be life-threatening, depending on the cause. If you’ve been exposed to bacterial meningitis and you develop symptoms, go to an emergency room and let medical staff know you may have meningitis.

If you’re not sure what you have and call your doctor for an appointment, here’s how to prepare for your visit.

What you can do

- Be aware of any pre- or post-appointment restrictions. Ask if there’s anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet. Also, ask if you may need to stay at your doctor’s office for observation following your tests.

- Write down symptoms you’re having, including changes in your mood, thinking or behaviour. Note when you developed each symptom and whether you had cold or flu-like symptoms.

- Write down key personal information, including any recent moves, vacations or interactions with animals. If you’re a college student, your doctor likely will ask questions about any similar signs or symptoms in your roommates and dorm mates. Your doctor will also want to know about your vaccination history.

- Make a list of all medications, vitamins or supplements you’re taking.

- Take a family member or friend along. Meningitis can be a medical emergency. Take someone who can help remember all the information your doctor provides and who can stay with you if needed.

- Write down questions to ask your doctor.

For meningitis, some basic questions to ask your doctor include:

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- What treatment do you recommend?

- Am I at risk of long-term complications?

- If my condition is not treatable with antibiotics, what can I do to help my body recover?

- Am I contagious? Do I need to be isolated?

- What is the risk to my family? Should they take preventive medication?

- Is there a generic alternative to the prescription medicine you’re recommending?

- Do you have any printed information I can have? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- When did you begin experiencing symptoms?

- How severe are your symptoms? Do they seem to be getting worse?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Have you been exposed to anyone with meningitis?

- Does anyone in your household have similar symptoms?

- What is your vaccination history?

- Do you take any immunosuppressant medications?

- Do you have other health problems, including allergies to any medications?

What you can do in the meantime

When you call your doctor’s office for an appointment, describe the type and severity of your symptoms. If your doctor says you don’t need to come in immediately, rest as much as possible while you’re waiting for your appointment.

Drink plenty of fluids and take acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) to reduce your fever and body aches. Also, avoid any medications that may make you less alert. Don’t go to work or school.

For more information Contact us

Leave a Reply